INTRO

I asked my friend Andrew, who is interested in art history, to write a short synopsis of the friendship and collaboration between Stanley Lewis, the Montreal artist, and Irving Stone the American writer.

Andrew did not know Stanley - he only knows what I have told him and what he has researched himself.

If I myself had not known Stanley, I would read Andrew’s summary and not think any more of it. Which got me thinking about what we know, and what we don’t know, about somebody. And what is missing between the lines.

Thank you, Andrew, for your writing and for bringing the information together in a way I simply cannot. I am not able to write like an academic - far from it.

However, knowing Stanley, there is more to the story, much more.

I knew Stanley, knew him well - he was my buddy - and I spent my entire time at film school working on a body of work about him and the world he moved in, in Montreal.

So I know the inside story between Stanley and Irving Stone.

In Part Two I will tell the story from Stanley’s point of view - it will not read quite in the same way.

So let’s begin . . .

Stanley Lewis, Irving Stone and Michelangelo

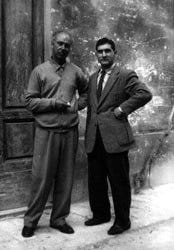

The American writer Irving Stone (1903-1989) is perhaps best known for his book The Agony and the Ecstasy (1961), a biographical novel about Michelangelo (1475-1564), which was later turned into a film (1965). What is less well known is that Stone derived most of his information about Michelangelo’s carving methods from the Canadian sculptor Stanley Lewis (1930-2006). Stone acknowledged this in the notes to his novel, writing that Lewis “was my guide in Florence to Michelangelo’s techniques; there he also taught me to carve marble. He has answered an unending stream of questions about the thinking and feeling of the sculptor at work”. This friendship between Lewis and Stone is a rare and interesting example of collaboration between an artist and a novelist, and undoubtedly contributed to the success of the book.

Lewis was in Florence researching and studying Michelangelo. He had come to Florence on a grant from the Greenshields Foundation in Canada, to develop his own skill as a sculptor and to add to his portfolio of work. Lewis enrolled in the studio of Vittorio Gambacciani, whom he called his Maestro, and who still practised the ancient techniques of marble carving.

Stone came to Florence at around the same time, also to research the life and work of Michelangelo. He used the streets and churches of the city as material for his novel, studied art in the museums, did extensive background reading, and made acquaintance with Bernard Berenson (1865-1959), the connoisseur of Italian Renaissance art who lived at Villa Tatti near to Florence.

Irving Stone and Stanley Lewis (Stanley Lewis archive)

Lewis’ Maestro, Vittorio Gambacciani, possessed a plaster cast of Michelangelo’s Tondo Pitti from which Lewis made a marble copy, now in the possession of Montreal’s Museum of Fine Arts. In a letter to his mother, Lewis wrote that this Michelangelo copy would demonstrate to everyone that he had had “a proper classical training”. The Tondo Pitti is partially unfinished, possibly because Michelangelo wanted viewers to see how the work had been created and to appreciate the marble for its own sake; and this may have been a factor which attracted Lewis to make a copy of it. Lewis loved marble as a medium and created an innovative series of sculptures in coloured marble. But Lewis’ use of marble for his sculptures also worked against him, because the use of this material made his work seem old fashioned back in Canada. As Lewis wrote to his mother, modern taste was for avant-garde “weird and welded metal toys”.

Michelangelo, Tondo Pitti, Bargello Museum, Florence (public domain)

When Lewis discovered that Irving Stone was in Florence, he contacted him and they arranged to meet. They had already met briefly in Mexico when Stone had bought one of Lewis’ prints. The friendship and collaboration between the two men was beneficial to both of them.

Over a two-year period (1957-58) Lewis gave Stone a great deal of information about sculpture in general and Michelangelo’s techniques in particular. He took him to the studio of Vittorio Gambacciani and gave him lessons in carving marble. For his part, Stone repaid his young friend by inviting him to dinners, at which they discussed art, lent him books, and introduced him to Bernard Berenson. And it was Stone who chose the title for Lewis’ most important sculpture, The Pink Lady.

According to Renaissance art theory, forms were imprisoned in the blocks of stone and crying out to be released by the sculptor. Michelangelo wrote that “we give to rugged mountain stone a figure that can live, and which grows greater when the stone grows less” (poem 152). Lewis expressed a similar thought when he wrote in a letter to Stone that “creative form . . . is realised by the slow process of peeling off layer after layer”. An idea repeated by Stone in his novel: “Bringing out the live figures involved a slow peeling off, layer after layer” (The Agony and the Ecstasy, Book 3, Chapter 8).

Renaissance Italians were keen collectors of fragments of ancient sculpture, because the spirit of the classical past seemed to live on in them. Lewis expressed a similar idea when he wrote to Stone that “ancient carvings are often found broken in several pieces, yet when they are assembled, its spirit, its soul still pulsates”. This idea was used by Stone, when one of the characters in his novel says that “many of my ancient pieces were found broken in several places, yet when we put them together their spirit persisted” (The Agony and the Ecstasy, Book 5, Chapter 8).

These examples demonstrate that Lewis and Stone were not only concerned with the mechanical techniques of sculpture but also with its aesthetics and philosophy.

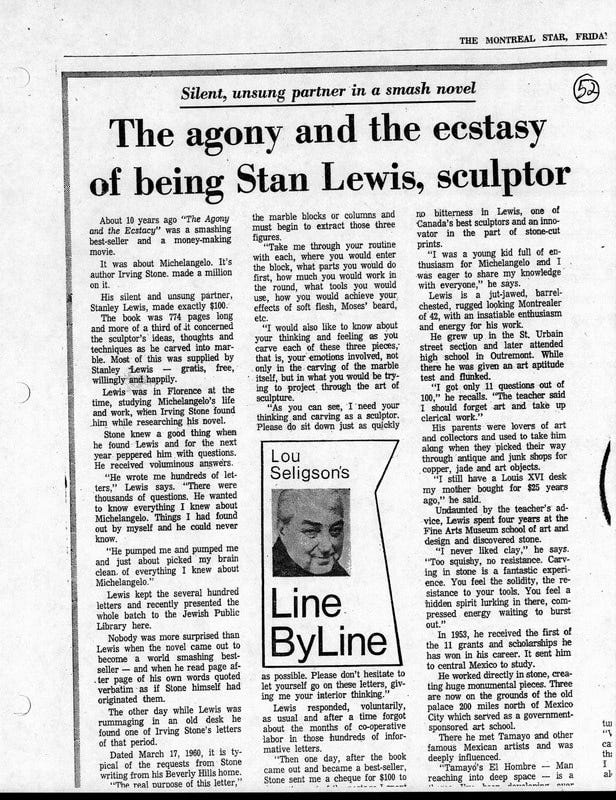

The publication of The Agony and the Ecstasy and the subsequent film made Stone a household name. He was also given an award by the Italian government for his services to culture. His classic novel The Agony and the Ecstasy is still in print and also widely available second-hand. Lewis, however, felt that he himself had not been given enough credit for his own contributions to the book, as shown by the newspaper clipping below:

Montreal Star, July 28 1972 (Jeanne Pope archive)

Although not given due recognition in his native Canada, Lewis was awarded a medal by the Italians and the Golden Key to the city of Florence for his contributions to Michelangelo studies, especially for his research into Michelangelo’s techniques. On a more personal level, he wrote to his mother to tell her about the beauty of Italy, the friendliness of the Italian people, and the ways in which his own art had developed as a result of his years in Florence: “I found myself in Michelangelo and Italy”.

Further information can be found in the website dedicated to the memory of Stanley Lewis - stanleylewismontrealsculptor.com.

Andrew Bailey

Thank you

Next week, Stanley’s version of the The Agony and the Ecstasy, which he would call

Behind the Agony and the Ecstasy

Have a great weekend. Have fun, enjoy, and see you next time.

LOVE ON YA!

JEANNE

Jeanne and Stanley in the Copacabana Bar, Montreal, 2005 (Jeanne Pope archive)

Thank you Andrew Bailey for putting forward your vision of the relationship between Stanley and Stone. And thank you Jeanne for unearthing Stanley from under the stones.

This is so fantastic! looking forward to next posts! xxx