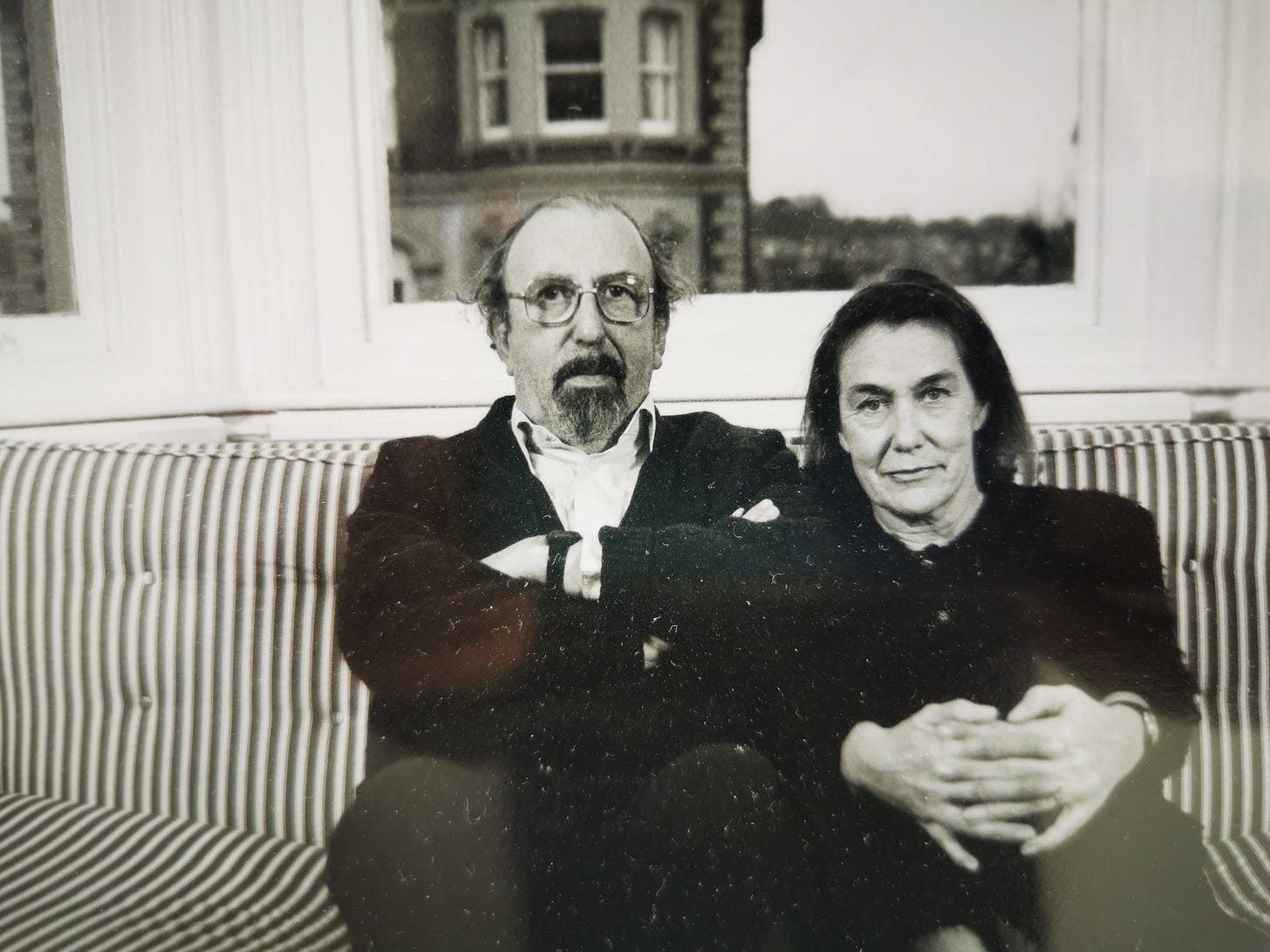

Pat & Marius - Mum and Dad

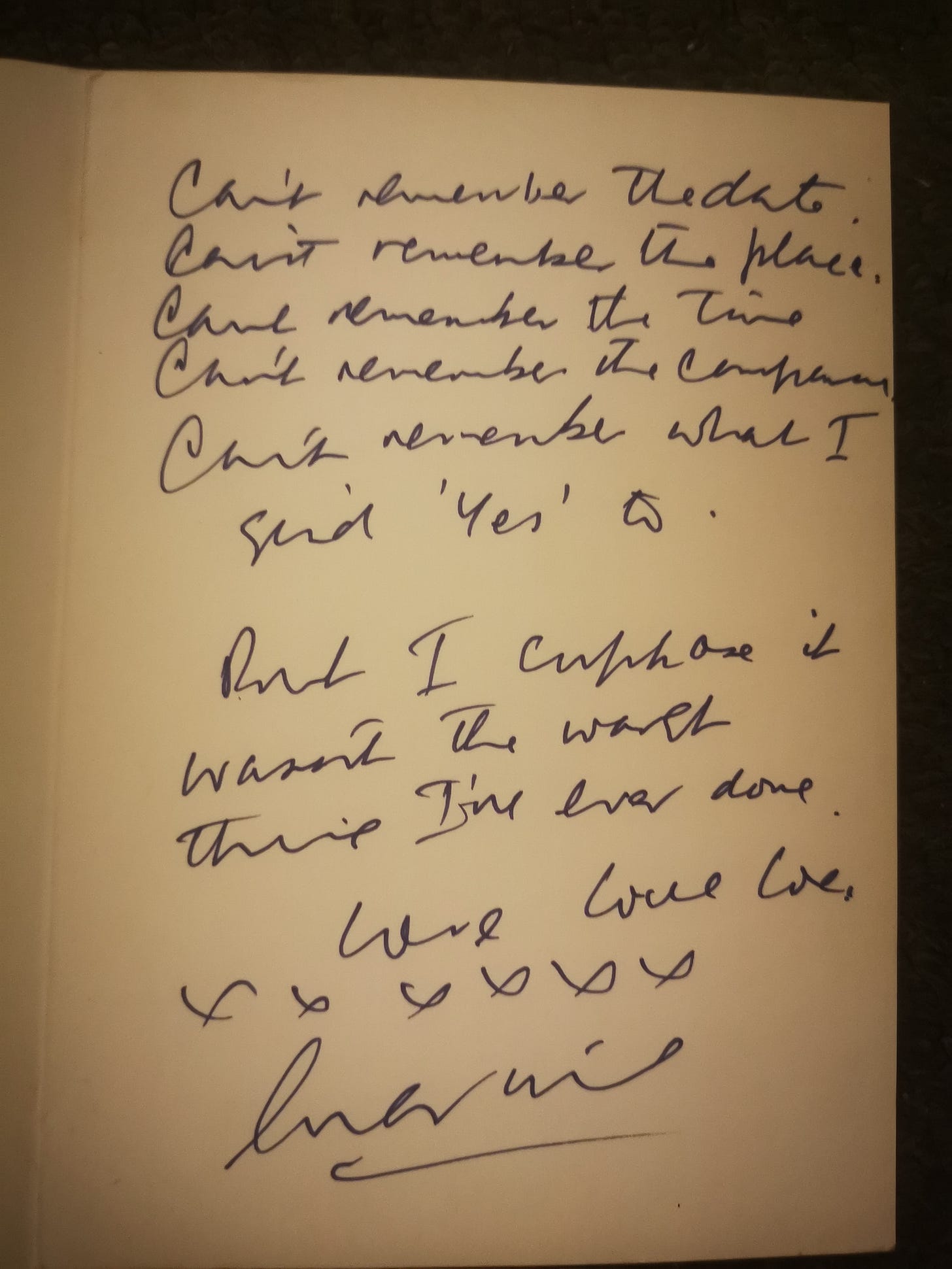

A card, Gurdjieff, Luba's Bistro, areoplanes, boats and the love affair

I saw my father's love card to my mother the other day. The one card my mother has kept, like a wedding ring, preciously. It is rather trite, and very my father; however, Mum loves it. "Typical Marius" she says. My father Marius was a cool man, a Capricorn, born in 1920, one of the G.I. Generation - The Greatest Generation. This was the generation where change erupted in the world no matter where. Innovation and novelty burst like spring blossoms. Dad would have heard the first crystal radio sets blast their tunes, used the first telephones, and boarded the first planes that crossed the African continent. The First World War had been and gone, but still was waiting in the wings for a second round. Dad always said to me, ingrained it into me, "take a chance on life".

There was license to create something new - really new. Like the age of Uranus or something which doesn’t exist, but it does if you want it to.

Dad’s childhood and youth were spent in South Africa, second generation. His grandparents had fled the Russian state of Lithuania. We think they came from the small town of Seda, where there had been a significant Jewish community since the eighteenth century. Dad lived apartheid badly, as many did, and he eventually left for good, in his twenties, to make his luck in Europe as a writer.

The journey to Europe was long, sometimes by bus, sometimes by plane.

The planes would land at short intervals along the 25 or more stops to London. According to Gordon Price, who wrote an interesting paper on incidental tourism, there were 72 flying hours, four or five aircraft changes, and about 2000 km of rail travel in-between. There were frequent weather problems, overnight stays, engine breakdowns, refuelling stops, which were often off the beaten track - which, as Price says, forced all travellers to become the incidental tourist. This all added visuals, tone and colours to Dad’s stories.

He told me it would take about ten days to stagger above the African continent, at times flying so dangerously low he imagined scooping the tops of the clouds like white candyfloss. The planes were noisy killer-machines - many people died in the first years of flying - yet thrilling and exciting, with a cabin crew shouting at the tops of their lungs into a megaphone to be heard above the din of the engines.

My brother Ivan insists that Dad only ever took the bus and train across Africa, I do recall him talking about the plane journey and the clouds.

At the same time, across the ocean the other way, due east as the swift bird flies, non-stop from South Africa to China, my mother was born to a French father and a British mother in the French Concession of Shanghai. There were no planes coming out of China for passengers, and so the journey was taken on ships leaving from Shanghai and arriving in Plymouth. (P&O liners did the Shanghai and Yokohama route.)

This three-minute clip comes from my full-length feature The Sea Hut. It is the last time my mother would cross this ocean because of the impending Sino-Japanese war.

She never went back.

(*I used all sorts of reconstruction to make the film which is 80 minutes long, with one year of painstaking research to find only public domain film and photos. I was based in China at the time and working around an unpredictable Internet.)

Jump forward to the 1950s, London, UK.

It is the wintertime and the London fog of 1952 which claimed 12,000 lives is still the winter devil. Immigration is just beginning on a larger scale and Dad is in his late thirties, zapping around Fleet Street writing fiction which never quite comes off, and ends up working on an assortment of newspapers and meeting the likes of Quentin Crisp and Francis Bacon, reading Jung's book Psychology of the Unconscious, and inspired by the writings of George Ivanovich Gurdjieff, the Russian philosopher. Dad was slightly marginal in the beginning, writing about LSD for the treatment of anxiety, depression, addiction, and psychosomatic diseases. He was fascinated by hypnosis and mediumship. Later, he became features editor for various newspapers. His great buddies were the Fleet Street cartoonists, and his dearest friend was JAK, also my Godfather.

There were three books by Dad’s bedside when he died: Dubliners - half-way through the last story, “The Dead” - Meetings with Remarkable Men by Gurdjieff, and a story about South Africa. This South African story was a tattered book, read many times; yet it has flown to some place unknown, as books do, along with the title which I cannot remember, even after going through every book title ever written by a South African or about South Africa.

Read more here for Meetings with Remarkable Men

I believe Dad loved Gurdjieff because he too was a wanderer, happy anywhere, any place his home, genuinely liking people, and slow to judge. One of our childhood mates, Grey, who has lived 40 years on the street, was a 14-year-old-often-runaway, who would often creep into my brother Ivan’s attic room to sleep the night when he couldn’t bear the thought of going back to his adoptive parents. He told me on countless occasions how Dad spied him there, but left the room staying nothing, lips sealed.

Dad was a man who busied round life without wanting anything more than to create, travel Europe in a camper van with his family, and try his hand at different artistic ventures.

Mum, ten years younger, flitted between Paris, London and Milan

where she worked as a secretary, then air hostess, and by the time she met Dad she was working as a waitress in the famous Gore Hotel restaurant called the Elizabethan Rooms, a mock-up of Elizabethan pageantry, wine, and song. This is where the Rolling Stones, ten years later in 1968, would launch their album Beggars Banquet. A cocktail called Sympathy for the Devil still sells here.

My parents finally met at the lively, small and beloved by many, Luba’s Bistro in West Kensington, London, where both were living. If you go to this link you will see what a typical night would look like. Famous then, remembered by many, cherished by my parents.

Luba was Gurdjieff’s niece, a white Russian émigré or first-wave émigré who ran from Red Russia, the uprising and revolution. Dad could connect as his family were Lithuanian.

Here is a lovely description of Luba’s from My Green Age by Terrence Keough

Dad came there on that warm night he first met my mother, who was with a friend. He came to meet other writers, artists, and the hurdy-gurdy set of London’s “left-bank” - and of course Luba herself. Luba was known to say to those who came to the bistro and wanted to know about her uncle: “Listen, here I can’t talk about my uncle. Here I can talk about food. You come here to eat. If you want to talk about my uncle, you come home when I’m ready.”

Mum remembers Luba’s with fondness, the long tables, the heat and excitement of the night, the ‘something in the air’ feeling. She recalls Luba’s larger-than-life character, charisma, bonhomie, and great cheap food. She often would make only one dish, take it or leave it. No-one left it - it was the place to be.

To know more about Luba’s life and her uncle, Gurdjieff, you can find out here at Gurdjieff Heritage Society.

Luba also has a cookery book/memoir which you can find here. She died in 1995.

I love the fact my parents met here, bustling and fun-filled. That they slowly fell in love.

Two immigrants making their way.

Mum and Dad married not long after meeting at Luba’s Bistro.

They loved for 50 years until Dad died in 2009 - a few days before his 90th birthday.

It snowed the day of his funeral, and snowed. They call it the Big British Freeze.

(On 16 December 2009 forecasters warned of very heavy snowfall to come. A band of rain moved southwards over the UK, which brought some snow. Snow fell in Kent, Surrey, Sussex. Wikipedia entry)

I love the snow.

I started this story with their love-card which I found the other day. Dad used to send it to Mum year after year on the day of their anniversary. It was his little joke.

After his funeral, Mum put it away.

Then, there it was again, propped by the radio on Dad’s side of the bed.

Inside, tongue-in-cheek as he was, is his love note to Mum.

Thank you so much for passing by and have a great week. If you enjoy, please pass it on. And be well.

With love,

Jeanne

UPDATE on Wake Li and THE CRACK - his feature length film

In 2021 I did a series of stories on Wake Li, my Chinese artist friend, and continue with a monthly diary blog which I put up on my website. This month he has sent a series of string black and white photos; if you have time, take a look here.

It is SO hard for Wake to get his work out of China, and I am delighted to say that his film The Crack, which we put onto YouTube for him, has had 64,977 views views since May 2021.

I am delighted for him.

He is amazed. NO-ONE was able to see it in China. He says:

Chinese movies, movies with high box office are just fun and entertaining. If films directed by Terayama Shuji, Fellini, Tarkovsky and other film masters were shown in Chinese theaters, no one would watch them. Moreover, thoughtful and critical films cannot pass the censorship of the State Administration of Radio Film and Television.

THE CRACK did screen once in the UK in December 2020 hosted by CICA Institute with the University of Manchester, but to a select university crowd.

You can read more @WakeLi - Scatterflix

Thank you for sharing your stories - and your family. Your account of their journey ( and film clips ) are informative and endearing. SLL - Wolfville, Nova Scotia

Dear Saralee, thank you so much for your comments. Merci beaucoup