It’s been three months since I came back home

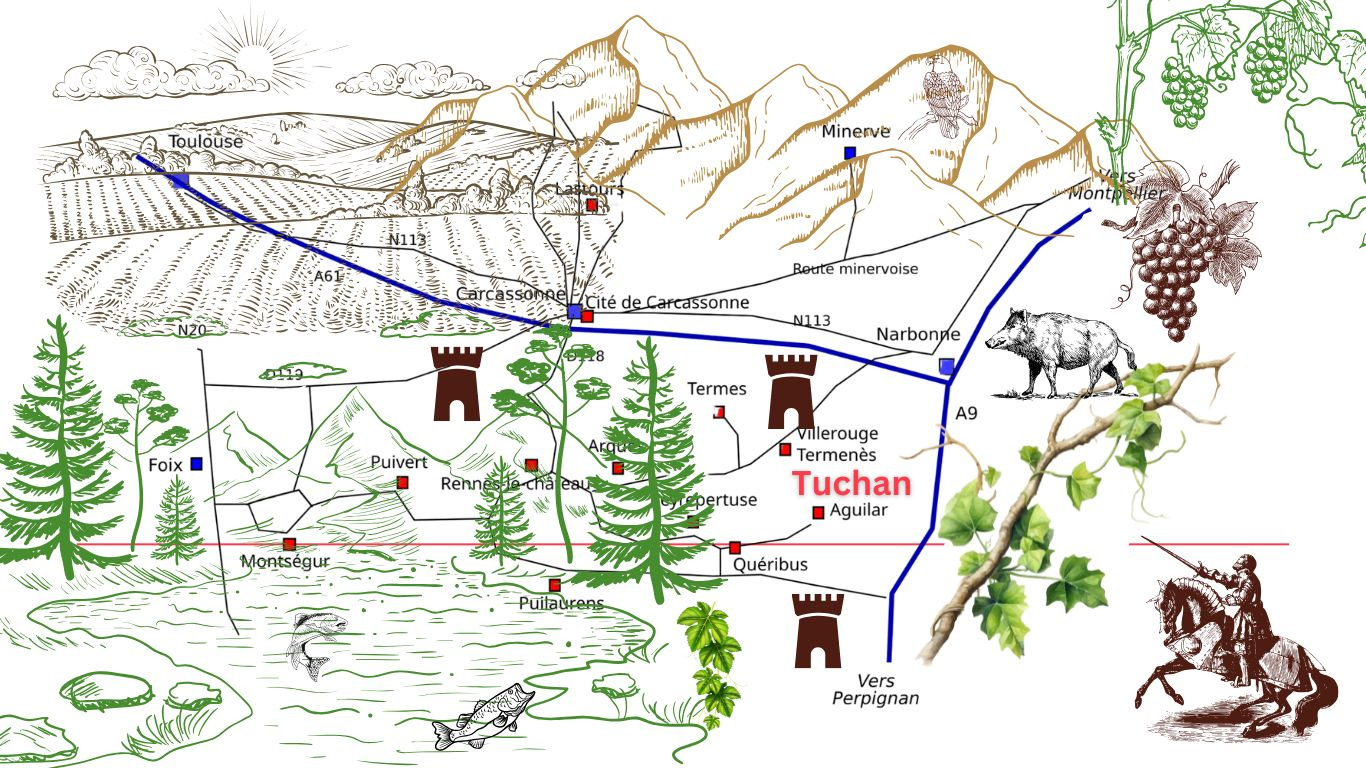

Home, the place in the south, the place where I wake early to write as the village slumbers deep. Tuchan. France.

In the beginning, when I first lived here, the clatter of life started at 6.00am. Now, it is Saturday morning and no sound, not yet the church bells, which are the constant reminder of life spliced into moments.

Things change, are changed, will change, have changed. To begin with, we are running short of water. It has not rained properly here in years. The last time I came home, three months ago, it rained, and I was able to film the downpour. It was like miners finding gold, the village was triumphant, for the gold of the village is wine and vines need water.

No rain, eventually no wine. No wine, no Cave Cooperative. No Cooperative, no work. No work, apathy. A village dies.

“Let’s look at it another way,” says Dani as she draws on her cigarello. Dani became Dani after being Dany for half her life. She has not completely transitioned, only half-way there as she has a fragile heart so the doctors told her she must not undergo a full change as the operation is too demanding on the body. Dani lives at the house at the end of the ruelle, the house we call ‘La Grotte.’ She has no idea why she bought it, on a whim, after years living on a boat, she wanted land; it was the first home she saw in a local paper, and snapped it up for 15,000 euros. She is the first trans to come and live in Tuchan. I am so glad she has come to our ruelle, is part of the ruelle tribe. She pivots between sea and land, land and sea, a few days here, and a few day in Sète further up the road.

Dani loves to talk and knows lots of things about lots of thing

Today she talks about about the weather cycles. “We had the Little Ice Age, which lasted a few hundred years and scarred the land, bringing revolts, death and desperation. So now is nothing new, an old habit in a new time. Humans are resilient.’

I research the consequences of this Little Ice Age I know nothing about: Historians suggest that Europe’s response to the Little Ice Age often manifested in violent scapegoating. Prolonged cold and dry periods led to drought, poor harvests, livestock losses, and a surge in disease. These hardships, combined with rising unemployment and economic struggles, created a vicious cycle of suffering.

Although some communities implemented strategies like diversified crops, emergency grain reserves, and international food trade, these measures were not always sufficient. As desperation grew, so did crime—robbery and murder became more common. In search of answers for their suffering, Europeans turned on marginalised groups, blaming them for famine, disease, and unrest. Research indicates that spikes in violence against these communities closely aligned with years of extreme cold or drought.

The local backdrop - Now

Nico lives up in his bergerie but is soon leaving, as there has been no sun for days on end. Imagine, no sun in the south? He has solar panels, but not enough to generate much electricity. He looks a bit weary tonight, and has come down to stay with a friend for the night. He comes in for a drink. Three years ago, when he moved out of the village, he was in love with the open air, the three-kilometre hike up the mountain, no water, just barrels brought up in his car. He was like a greedy child, boasting about his bonne heure. But today, he is tired. He plans to sell up and move to the sea.

In the local shop,

the shelves are half-empty—or half-full, depending on how you look at it. The shelves are a sign that things are changing along the food chain. Additionally, a new supermarket has opened seven kilometres away, offering much more for much less.

The young lad who works there full time pops round to see Valentin. I ask him about the Spar, ‘have you seen a big difference with the tourists?’ “Of course, there’s not enough water, we can not fill the swimming pools so people are going to Spain, Portugal, anywhere. They won’t come here.”

Chez Patrick,

the butcher, has closed as he’s retired. The meat is not so good at the Spar. The tabac is closed, so to buy cigarettes, people drive to Spain and then sell contraband baccy in the village. 8 euros a pack instead of 13 euros.

It all seems sad. This time last year, there was some hope. Right now, it feels very uncomfortable, I don’t even really want to film. It’s hard. Romain who works at the cave will have a chat tomorrow, the day France meets Italy in Rugby, the one day of the week the bar will be full, water for the moment, forgotten.

But it is February,

and the village folk are worried. Some of the viticulturists have taken out salary insurance, others are pulling up their vines, though the year has only just begun. Romain tells me that the harvest was half what it was.

It’s easy to be pessimistic, there is a lot to be pessimistic about, with what we know and what we do not know. What to do in these moments?

CREATE something

I have no internet and that is OK. I love coming home to detach from the demands of the city. Home is this kitchen, hardly changed since the 17th century, with paper, pens, and paint waiting in the corner and Valentin, the gypsy who calls himself Momo, who lives here for 20 years, is also a part of her history, a part of her. Even if I wanted him to leave, he would take the house with him.

I ask him to help me paint the kitchen. We turn on Chérie FM, open long-forgotten boxes, and laugh over old memories and poems never sent to unrequited lovers. He shares the village gossip, who is in love with whom, who has run off with who, and as we stand side by side, we forget the non- rain for a while, two old friends painting in unison, knowing each other so well.

When we first met years ago, the village was a garland of magic, so far off the beaten track it wasn’t even on the map. When you arrived, you either stayed or moved on. It’s one of those places that is either scorching hot, so hot you fall in love, or it leaves you cold. Even now, in this time of little water, it holds its grip, weaving it’s invisible claim on our hearts. We are loyal, we are in love.

We are Tuchanais

The village has passed from the Carthusian Monks of the 10c who first planted the vines and cultivated valleys with rich clay- calcaire filled to the brim, to the Parfaits- Cathars, the Spanish fleeing Franco, the Italians escaping Mussolini, the Algerians who stayed after Algerian independence, and the gypsies, like Valentin, both sedentary and travelling, each leaving their mark.

I fit in well to this mix. Of mixed heritage, not quite knowing exactly where I belong, I fell in to Tuchan with my daughter years ago, and never left. Even when I am not here, I see from the corner of my eye my village and little home in the ruelle, and not far off, Valentin somewhere where he has everything from a meter of hemp-string to seeds from the Senegalese Baobab tree. And wine in vats from every winegrower in Tuchan. I smell each bottle—some sweet, some fruity, and some already turning to vinegar; destined to become vinegar.

Sunday

We have finished the painting; it looks swell. The house always smiles after a paint job. Her walls are so old and full of crevices, which I will never plaster over, as it would erase 300 years of history, of life.

Walls breathe, walls have secrets—implanted, imprinted.

Paul Henri-Kiki keeps ringing, he wants us to come up to the bar to watch the Rugby, France V Italy. We have the radio on the radio a friend gave Valentin from his mother who was Dutch, from the 1970’s. It has one hell of a lovely deep sound.

We give in, the bar calls. I love Sunday rugby days. The spirit is just rising! Paulo the Star, the brightest star who grow up in our ruelle, kicks the day off.

Kiki, one of my subjects of the next film - The Time of The Water - Le Temps D’eau

The Film - a quick résumé

I go to the UK tomorrow. Leaving Tuchan is leaving another world, a wild, untamed world of men, rugby, hunting, and romance.

I wonder how we will live if the wine runs dry.

I have begun my second film, the prequel to Le Temps Des Vendangeurs. Initially, it was to be called Le Temps Des Gens - The Time of the People - but it is now Le Temps D’Eau—The Time of Water. I need to understand why the village has not harnessed its most precious resource, water, and why it has not created sunken reservoirs to collect its liquid gold.

At first, I thought people would be reluctant to talk, but they want to talk. In Tuchan the villages have turned their signs upside down, it is their silent cry, a world flipped on its head. The wine growers, burdened by policies, use this gesture to speak where words fail. They are saying: our way of life is under threat. A call for action, a plea to be heard. So, I shall film the cries…

The film will intertwine with village life as it continues; rugby, love, life, and dreams, all seen through the eyes of different Tuchanais. Going back to their roots, to austerity and new ways of creating things, and like thier ancestors who planted vines, had dreams and carved some hope, hope will be found, as Dani says,

Humans are resilent.

We all got home at 12.00am

The bar was a jive!

Monday

Dani takes me to the airport. She is going to the sea for a few days. There is a deviation and we pass through the back mountain roads. Once we pass Carcassonne it is like a curtain pulls back and there is rain, and vines become pastures shimmering envious green.

Then the plane.

Till April calls and I come back.

Thank you so much for reading and sharing. I discovered why sometimes you are unable to post comments directly on my Substack. I’ve now adjusted the settings so you should be able to.

I truly appreciate any words or suggestions, and I’m grateful to you all for keeping me writing. I love sharing these stories.

From last month.

Tao’s Papa passed away just after I came back from China. I am so happy I made that Travel to Tao journey.

Have a great month. Watch for the

Planetary parade: Mercury falls into line for rare seven-planet alignment

Love, love, and Love,

Dear Jeanne,

Your writing paints such a vivid picture of both the beauty and the struggle in your village . It’s heartbreaking to think that such a warm and wonderful community, with its rich traditions and hardworking wine growers, could be at risk due to the lack of water. Your writing captures the soul of the region so beautifully, and I hope to visit one day to experience it firsthand. Let’s hope for a solution that will sustain this special place for general to come.

I wish we could send you some of the rain we have had here in England. I don't know how anyone can deny the reality of climate change and its disastrous effects.